Posted by Tamsyn Strike

User Experience (abbreviated to UX) is how a person feels when interfacing with a website, web application or software. The job of a UX designer is to analyse and evaluate how those people feel about that system; their needs, wants and limitations.

As human beings, we’re all different, and what works for one person might have the opposite effect on another. For this reason, UX Design is not one-size-fits-all. It can’t be manufactured, imposed or predicted; it must be tailored to create specific experiences and promote certain behaviours.

Good UX Designers should efficiently reduce friction between the task someone wants to accomplish, and the tool that they are using to complete that task.

Cognitive psychologist Donald Norman is often called the inventor of User Experience, but the beginnings of UX actually started much earlier than this.

In the late 19th and early 20th Century, during the ‘Machine Age’, when corporations were growing and skilled labour was declining, advances in technology was inspiring industry leaders to become more efficient.

One of those industry leaders was Frederick Winslow Taylor, an American mechanical engineer who became one of the world’s first management consultants. Taylor applied his engineering principles to work done on the factory floor, thinking that by analysing the work he would find the “one best way” to do it.

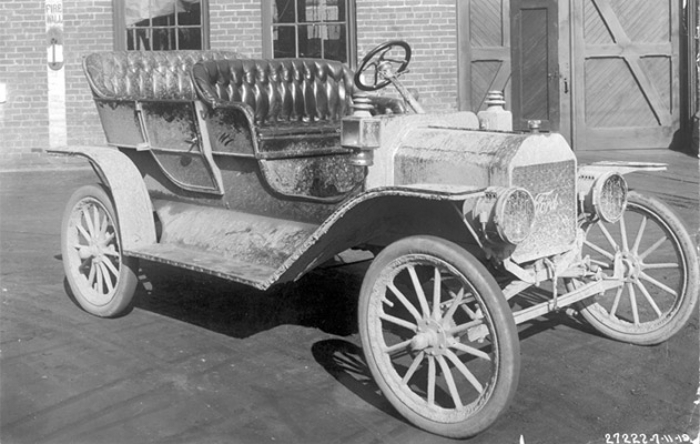

Another prominent industry leader of the time was Henry Ford. Ford was the creative force behind the growth of the automobile industry. With the Ford Model T, he transformed craft production into mass production by standardising the output, using conveyor assembly lines and breaking the work into small, deskilled tasks.

Both Taylor and Ford created more efficient and routinised processes by researching the interaction between workers and their tools: an early precursor to UX. However, they were criticised for dehumanising their users (the workers) in the process and treating them like cogs in a machine. It wouldn’t be until the 1940s that the user would be taken into greater consideration.

The First and Second World Wars saw emerging research into ergonomics and human factors in aviation, particularly focused on the design of equipment and how best to align it with human capabilities. During this period Paul Fitts, a psychologist who served in the US Air Force, helped develop a formula that predicts the time required to move to a target, determined by its distance and size. The formula was coined ‘Fitts’ Law’ and led to recommendations for the most effective organisation of cockpit controls.

Around the same time, industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss wrote Designing for People: an autobiography that discusses Dreyfuss’ design philosophy. In the introduction, he lays out the basic task of the designer, which was posted on the wall in his offices:

“What we are working on is going to be ridden in, sat upon, looked at, talked into, activated, operated, or in some way used by people individually or en masse. If the point of contact between the product and people becomes a point of friction, then the industrial designer has failed. If, on the other hand, people are made safer, more comfortable, more eager to purchase, more efficient — or just plain happier — the designer has succeeded… And if he designs enough things in good taste, he brings better living and greater satisfaction.”

Later, this same philosophy, alongside Fitts’ Law, became the basic laws of physics for User Experience designers. But how were these applied to the digital age?

During the early 1970s, Xerox – a company mainly associated today with printers and copiers – founded PARC, the Palo Alto Research Centre. PARC is responsible for the development of laser printing, Bitmap graphics, Ethernet and the computer user interface, featuring windows and icons, operated with a mouse. From these developments Xerox produced the Alto, one of the first personal computers.

The Xerox Alto was not a commercial product, but several thousand units were built and heavily used at PARC, Xerox and several universities for many years. It greatly influenced the design of personal computers in the following decades, most notably the Apple Macintosh; leading us back to Donald Norman.

Norman studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he received a Bachelor of Science degree in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and a Master of Science degree in Mathematical Psychology. He applied his knowledge to the emerging discipline of cognitive science, an interdisciplinary scientific study of the mind, combining ideas and methods from psychology, computer science, linguistics, philosophy and neuroscience. Norman went on to found the Institute for Cognitive Science, establishing himself as a consultant and writer.

In 1981, his article ‘The Trouble with Unix: The User Interface is Horrid' was published in Datamation magazine and catapulted him to a position of prominence in the computer world. In 1993 Norman joined Apple. Various accounts from people working there at the time report that Norman introduced user experience to encompass what was previously described as human interface research. He held the tile User Experience Architect, probably the first person to ever have UX on his business card.

“I invented the term because I thought Human Interface and usability were too narrow: I wanted to cover all aspects of the person’s experience with a system, including industrial design, graphics, the interface, the physical interaction, and the manual.”

Norman uses the term “user-centred design” to describe design based on the needs of the user, leaving aside secondary issues like aesthetics. User-centred design involves implying the structure of tasks, making things visible, getting the mapping right and designing for error, and it’s these fundamentals that led to UX design as we know it today.